|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The XVII Century

Freedom of interpretation

|

ortuguese tile painters used engravings of ornaments they received from elsewhere in Europe to create ceramic coverings destined for large wall surfaces - a task which required an imaginative transposition of scale. ortuguese tile painters used engravings of ornaments they received from elsewhere in Europe to create ceramic coverings destined for large wall surfaces - a task which required an imaginative transposition of scale.

The XVII century images produced in this way include the so-called ?grotesques" - secular motifs from ancient Rome which had been recovered a century earlier by the painter Rafael in order to decorate the Vatican. Widely disseminated around Europe, in Portugal they were employed in the tiling of churches, albeit incorporated into religious themes.

Their fantastic nature made these "grotesques" popular with a people which was then in close touch with distant cultures. This was also the reason why the tile painters sought inspiration from chintz - a type of exotic printed calico from India used as an antependium in front of altars - which they transferred to their ceramic work. These designs were often used in conjunction with western themes and adapted to a Catholic symbolism in what constitutes one of the most interesting cases of transculturation in the Portuguese decorative arts.

|

|

|

|

|

Santo Amaro Chapel,

Lisboa, 1670 · 1680.

foto: Paulo Cintra e Laura Castro Caldas

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

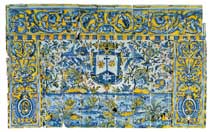

The frontispiece of an altar,

2nd quarter of the XVII century,

MNMC cat. 1439.

photograph: José Pessoa (DDF-IPM)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

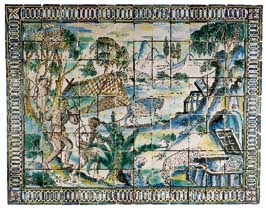

"The Leopard Hunt",

3rd quarter of the XVII century,

MNA cat. 137.

photograph: José Pessoa (DDF-IPM)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Carcavelos Parish Church,

1650 · 1675.

photograph: Nicolas Lemonnier

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The frontispiece of an altar,

Our Lady of Hope Convent,

Alcáçovas,

2nd quarter of the XVII century.

photograph: José Pessoa (DDF-IPM)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

© Instituto Camões, 2000

|

|

|

|

|