|

St. Elmo’s Fire in the Literature of Journeys

THE “LITTLE VAPOUR, OR AERIALL FUME”, IN THE WORDS OF CAMÕES, APPEARS FREQUENTLY IN PORTUGUESE LITERATURE

|

|

|

|

The first written reference to the brightness known today as St. Elmo’s Fire is possibly that which appears in the “Hinos Homéricos”, a collection of poems in Homer’s style written by several unknown authors. Here they are referring to the mythological twins, ”Castor the horse breaker and the innocent Polux, sons of Zeus and glorious sons of Leda of the beautiful walk”. During storms it is said that the mariners pray to these “sons of the great Zeus, consecrating white lambs and moving towards the prow; the strong wind and the massive waves keeping the ship under water until, suddenly, they are both seen in the air, quick as a flash and with golden wings. They immediately soothe the cruel gusts of wind and calm the waves of the white sea: they are beautiful signs and a salvage”.

For the Greeks, the brilliance on the ends of the masts that could be seen at stormy moments could be the sign of a bad omen, when the light had only one tip, in which case it associated the phenomenon to Helena, the sister of Castor and Polux. However, this brilliance was the sign of a good omen when it had two tips, in which case it was associated to the mythological twins. According to the legend, they had some sort of power over the forces of the storm and were therefore considered as the mariners’ protectors.

In his “Metaurus”, Aristotles describes the same phenomenon and Pliny the Elder (c. 29–79 d.C.), the great Roman encyclopaedist, refers to it in some length in his “Natural History”, confirming that “if it is one, it announces a severe storm”, but “if there are two, and this when the storm has already worked itself up, is a good sign”.

In the comments of Julius Caesar, the phenomenon is described as witnessed on earth: “In the month of February, somewhere around the second half of the night, suddenly a dark cloud stirred itself up, followed by a hailstorm, and in the same night the tips of the lances of the V Legion appeared to catch alight”.

|

|

|

|

Centuries later, already in the Christian era, the navigators of the Mediterranean saw in this mysterious fire the sign of the intervention of the Hold Spirit through Saint Erasmus, an Italian bishop murdered in 303 A.D., also known as Saint Elmo or Sant’Elmo.

In the times of the Discoveries, the Portuguese and Spanish mariners would take on another saint of the Catholic Church as their protector, a Dominican friar of the thirteenth century by the name of Pero Gonçalves. Over the years, the legends blended and the name “Telmo” was juxtaposed. At the end of the sixteenth century, people spoke of Pero Gonçalves Telmo, as if that had always been his name.

Portuguese literature is filled with references to this saint and to the bright phenomenon. Starting with the accounts of the journey, it is worth highlighting what D. João de Castro, the great intellectual traveller of the sixteenth century, wrote in the Guide to Lisbon and Goa of 1538.

“Returning to India a second time, in the year 1545, on that same night the sign which the mariners call the Holy Spirit appeared twice, lasting for a half hour. First we saw it on the tip of the upper mast of the topsail, and then on the yardarm of the spar, and then on the tip of the mast of the topsail and then on the shrouds and stays of the vessel. This semblance which they call the Holy Spirit was a light as big as the one normally made by a lamp or candle, but its light was not red like fire but silver, like that which can be seen on the moon; and, whenever there was a flash of lightening, this sign did not appear. However, as soon as the splendour of the flash of lightening passed, it appeared once more. When this sign appeared to us, it was drizzling and the sky was dark and dense, and it was easy to see, not deceiving anyone, and it seemed a mystery and secret of nature. By this time we were in a north-south direction to the Rio do Infante and at an altitude of 34º.”

|

|

|

|

|

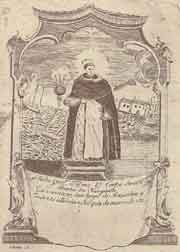

"Saint Elmo Saving the Castaways", an oil painting dating back to around 1714 found in the chapel of the Palácio do Corpo Santo, in Setúbal. Note the rainbow, correctly coloured, and the candle in the hand of the saint.

|

In the “História Trágico-Marítima“ there are several interesting references. In the account of the castaway of the ship Santa Maria, an anonymous narrator describes the extreme belief of the mariners. “All the men of the sea have great reverence for the Blessed Saint Frei Pero Gonçalves, and have him as their advocate in the torments of the sea, who believe with all their heart that those exhalations which in the good and bad times appear above the masts, or in other parts of the ship, are the Saint who comes to visit them and to console them. And, when they do indeed see that exhalation, they all run to the deck with loud screams and shouts, saying: “Hail, hail, Holy Spirit”. And they go on, saying that when they appear in the high parts, and there are two, three or more exhalations, it is a sign that he will give them fine weather; but, if only one appears, and in the lower parts, it announces a shipwreck. And they believe this so strongly and so firmly that when these exhalations appear on the upper masts, the mariners climb up the masts and declare them to have drops of green wax; but they do not bring them, nor do they show them. Or at least we do not ever get to see them. And if the religious men on board the ship wish to draw close to them, giving them reasons to show them that these are exhalations, and declaring the natural causes that bring them about and make them appear, there is nothing left but to take up their arms and to fight against those who contradict their faith, which is the reason why they have it.

Another account in the same collection is that of Henrique Dias, servant of D. António, Parish-Priest of Crato, in the Account of the Journey and Shipwreck of the Ship S. Paulo, which left India in 1560:

«[...] which light, seeing the quartermaster and mariners of the prow began to save from God and Our Lady and their Saints, in very loud voices to which everyone replied with loud wails and tears [...] And so the night went on in these wails and outcries, the lights following us always.”

|

|

|

|

Fresco on the ceiling of the same chapel showing Saint Elmo helping a castaway.

|

|

In eastern Ethiopia, of Frei João dos Santos, the adventures of the ship of S. Filipe, which had left Lisbon in 1586, are described.

“[On a stormy night] the Holy Spirit appeared on the spar of the large mast, in the form of a spark of fire, very clear and very bright, and there, in everyone’s sight, it moved to the mast of the mizzen sail, where it saved the pilot of the ship, from the chair on which he was commanding, saying: Hail, Holy Spirit, hail: have a safe journey, have a safe journey. And all the others who were on board the ship and who were present, replied in the same manner: Have a safe journey, have a safe journey, with many tears of joy. This bright light remained in this place for a long time and then disappeared from everyone’s sight.”

Further ahead, one reads of the conflicts between mariners and prelates, which this extreme belief may unleash. At a certain point during the storm, a soldier kneels before the light and hitting his chest repeatedly exclaimed: “I love you, my lord Pero Gonçalves; you have saved me from this danger by your compassion”. The priests on board the ship warned him that he should not pray in this way, as only God should be adored and not the saints. But the soldier replied: My God shall now be the one who saves me from this danger.”

In the Portuguese literature there are also several interesting references to St. Elmo’s fire. Gil Vicente, in Act II, Scene I of the “Triunfo do Inferno” has a mariner scream, to the sound of a devilish high wind:

"Ei-lo precioso santo

Frei Pero Gonçalves Bento

PILOTO:

Empara-nos de tanto vento

C’o teu precioso manto

Senhor, libra-nos a malo

GREGÓRIO:

Dêmos à bomba, piloto;

Dai ó demo Frei Gonçalo,

E não Frei Pero Minhoto

PILOTO:

É o bem-aventurado

Frei Pero Gonçalves bento."

Camões speaks of St. Elmo’s fire, which he describes as "A little Vapour, or aeriall Fume” in the first two verses of stanza 18 of Canto V of The Lusiads. The reference can be found in the account by Vasco da Gama to the king of Melinde, in the part in which he describes the fantastic experiences witnessed by the narrator:

"I saw (as plain as the sun's midday light)

That fire the Sea-man saints (shining out faire

In time of Tempest, of feirce winds despight,

Of over-clowded Heavens, and black despayre):

Nor did wee all lesse wonder (and well might,

For twas a sight to bristle up the Hayre)

To see a sea-born Clowd with a long Cane

Suck in the sea, and spout it out againe."

"I saw with these two eyes (nor can presume

That these deceiv'd mee) from the Ocean breathed

A little Vapour, or aeriall Fume,

With the curld wind (as by a Turnor) wreathed.

I saw it reach to Heaven from the salt spume,

In such thin Pipe as those where springs are sheathed;

That by the Eye it hardly could be deemed:

Of the same substance with the Clowds it seemed."

Bocage alludes to the belief in the sonnet Deprecação during a storm:

”Oh Deus, oh Rei do Céu, do mar, da terra

(Pois só me restam lágrimas, clamores),

Suspende os teus horrísonos furores,

O corisco, o trovão, que a tudo aterra:

Nos subterrâneos cárceres encerra

Os procelosos monstros berradores,

Que, enchendo os ares de infernais vapores,

Parece que entre si travaram guerra.

Para nós, compassivo os olhos lança,

Perdoa ao fraco lenho, atende ao pranto

Dos tristes, que em ti põem sua esperança!

Às densas trevas despedaça o manto,

Faze, em sinal de próxima bonança,

brilhar no etéreo tope o lume santo.”

And Afonso Lopes Vieira, in a paraphrase of an account of the “História Trágico-Marítima”, calls our attention to the forgotten past and laments the faint-heartedness of the cult of S. Pero Gonçalves:

”Por te enramarem coentros,

Entre bailes e folias,

Tu às hortas de Enxobregas,

São Frei Pero, de antes ias.

Assim nos guies e salves,

Senhor São Pero Gonçalves!

Pelas outavas da Páscoa

Era o teu dia marcado ;

Vinhas então de Enxobregas

De coentros enramado.

Assim nos guies e salves,

Senhor São Pero Gonçalves!

Bailando por São Frei Pero,

Não havia homem do mar

Que não tecesse capela

Para ao redor a levar.

Assim nos guies e salves,

Senhor São Pero Gonçalves!

Que tamanha devoção!

Mas São Pero, no mar

Acendia a luz nos mastros

Para a tormenta amainar.

Assim nos guies e salves,

Senhor São Pero Gonçalves!

Quando se lá acendia,

Essa benta luz de encanto,

Todos no convés em grita:

— Salva, salva, oh Corpo Santo!

Assim nos guies e salves,

Senhor São Pero Gonçalves!

Mas São Frei Pedro, esquecido,

Já não vai às hortas, não;

Não tem bailes nem folias,

No mar não tem devoção.

Assim nos guies e salves,

Senhor São Pero Gonçalves!

Por isso as naus se desgarram,

Santo nome de Jesus!

Salva, salva, oh Corpo Santo,

Acende ao alto a tua luz!

Assim nos guies e salves,

Senhor São Pero Gonçalves!”

There are many unequivocal literary and popular references, as many as there are travel stories. The stories refer to a genuine atmospheric phenomenon, today called St. Elmo’s fire. A phenomenon so interwoven in the Portuguese history and literature that it contains many of the historical descriptions that contributed to its scientific knowledge.

Nuno Crato

|

|

|