|

The 60s

|

|

|

Lourdes Castro, Sombras projectadas (de Lourdes Castro e René Bertholo), Rue de Saints Pères, Paris, 1964.

DR/ Cortesia Assírio & Alvim.

|

|

Salazar's dictatorship, whether one considers it as fascist or not, was perhaps not as ferocious and less spectacular than its European counterparts. However, it was definitely the longest (1926-1974) and as mutilating on all areas of Portugal's economical, social and cultural development. Except for a few moments limited in time this was a period in which the official altitude was that of seclusion in relation to the international trends that constructed the history of modernity.

There were effective changes and revitalization within the artistic circles in a strict sense, thanks to the exceptional cases of artists who emigrated abroad and to the few moments when Portugal allowed openings, however small they were. Although not much changed within the more generalized context. Portugal had a poorly educated population, a massively disinformed public opinion, a conservative official culture and the opposition was becoming increasingly a cultural anachronism.

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, where the visual arts are concerned, one witnessed the dragging of a burgeoning Modernism constantly struggling against a deep-rooted Naturalism and lyrical Romanticism. A unique light would then only shine during the second decade of the century with the work of Amadeo de Souza-Cardoso, alongside with that of Almada Negreiros. This happened within the framework of events related to the so-called "Orpheu" generation, also spurred by the presence of the Delaunays in Portugal after World War I.

| |

|

| |

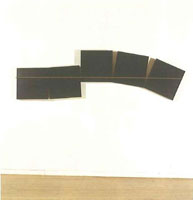

Noronha da Costa, S/ título, 1968. Madeira, óleo espalhado e acrílico, 30,2 x 35,4 x 18 cm. Col. Fundação de Serralves, Porto.

José Manuel Costa Alves.

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Fernando Lanhas, 042-69, 1969. Óleo sobre madeira, 98 x 148 cm. Col. Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian / CAMJAP.

Mário de Oliveira.

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Menez, Henrique VIII, 1966. Óleo sobre tela, 180 x 210 cm. Col. Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian / CAMJAP.

Mário de Oliveira.

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Paula Rego, Salazar a Vomitar a Pátria, 1960. Óleo sobre tela, 94 x 120 cm. Col. Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian / CAMJAP.

Mário de Oliveira.

|

When Portuguese society reached the 60s, it was kept away from the international circuits of artistic production and circulation, and deprived from access to exhibitions or other initiatives. Thus, the public opinion could not attain a fundamental artist education and neither could the specialized audience be given more up-to-date information and direct experiences with contemporaneity.

Facing the continuation of the dictatorship under Marcelo Caetano's government (1968-1974), the feeling was that of disappointment. A growing discontent was also felt due to an absurd and unsolvable colonial war that began in 1961. In the cultural spheres, in the students' milieu and amongst the youth in general, frustration was growing; was spreading with the aloofness with which the State treated the major social and cultural turnabouts that the decade had experienced internationally.

The rise and death of President Kennedy, the political and ideological battles for Vietnam, the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, the hippie movement, the pop revolution and May 68 - only the distorted, censored echoes reached Portugal through the minute urban cultural elites.

In the visual arts, the 60s were an epoch of experimentation, of the convergence of several aesthetic movements and trends, namely pop art, the "nouveau réalisme", op art, minimalism, conceptual art, art povera, video art, performance, body art and land art. It is also the decade of the death of Duchamp (1968).

Within Portuguese context the 50s had been a period of the continuity of previous aesthetic solutions focused on the persistent dialectics between figuration and abstraction and whose protagonists were split, by and large, between neorealists, surrealists and abstractionists.

It is in this circumstance that the oeuvre of Maria Helena Vieira da Silva, an original blending of figuration and abstraction, strongly personalised, emerges as the grandest expression of this period. It would also be present significantly in the following decades.

In the 60s, one would witness the growth of a new artistic situation specifically underlined by the emergence of a new generation of artists and cultural agents. Also, the consolidation of new tendencies of national artistic production reflected the need to be in tune with international languages, largely due to the emigration of a great number of artists, something that also would occur throughout the 70s.

To leave one's country temporarily or permanently in accord to the general emigration flux of the time was the option of many artists. They did this for political reasons, as a solution sought for a career or even to simply come into contact with new but inaccessible tendencies. In this circumstance, one should mention that England welcomed António Areal, Rolando Sá Nogueira, Mário Cesariny, Menez, Paula Rego, João Cutileiro, Bartolomeu Cid dos Santos, Ângelo de Sousa, Alberto Carneiro, Eduardo Batarda, António Sena, João Vieira, Ruy Leitão, João Penalva and Graça Pereira Coutinho. As for Lourdes Castro, René Bertholo, Costa Pinheiro, Escada and João Vieira, this group would meet in Paris, where they would assemble the KWY group; this same city was visited by António Dacosta, Júlio Pomar, Jorge Martins and Manuel Baptista.

A certain effort of renewal opened the way to an approach towards international art. Moreover, the newly-founded Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation aided substantially through scholarships, allowing for the emigration of these artists. There was a new mode of looking at the artistic phenomenon, from the largest collective exhibitions of the time (opening the decade, in 1961, the 2nd Exhibition of Visual Arts at the Gulbenkian Foundation) to the establishment of new art galleries that brought new dynamics to the Portuguese market.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Maria Helena Vieira da Silva, Les Degrés, 1964. Têmpera sobre tela, 194,5 x 130 cm. Col. Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian / CAMJAP.

Mário de Oliveira.

|

|

Lourdes Castro, Caixa de alumínio em caixa de aguarela, 1963. Assemblage, 52 x 52 cm. Col. Mr. e Mrs. Jan Voss.

DR/ Cortesia Assírio & Alvim.

|

|

Armando Alves, Objecto, 1969. Madeira pintada, 100 x 63 x 34 cm. Col. Fundação de Serralves.

DR/ Cortesia Fundação de Serralves.

|

During the first half of the decade only the gallery of the daily Diário de Notícias (in Lisbon), the Divulgação Gallery (in Lisbon and Porto, and whose director was Fernando Pernes), the Alvarez Gallery and the artists' association Árvore (both in Porto) gave for the first time small steps towards the marketing of visual artists. Only in 1964 with the newfangled experience of the bookshop-galleries such as Buchholz and Galeria III, and after the opening of new galleries in the turn of the decade, the new art market would stimulate artistic practices.

Nonetheless, one would have to wait for the instauration of democracy to sever the ties with an extended unsustainable situation but whose most profound transformation, heralded by the aesthetical ruptures of many artists of the 60s would only have its most effective cultural consequences after the post-revolutionary convulsions in the early 80s.

|

|

|

|

|

|

José Escada, S/ título, recorte azul, 1968. Papel recortado sobre papel, 31,5 x 48 cm. Col. Caixa Geral de Depósitos.

Laura Castro e Caldas e Paulo Cintra.

|

|

José Escada, S/ título, recorte rosa, 1968. Papel recortado sobre papel, 31,5 x 48 cm. Col. Caixa Geral de Depósitos.

Laura Castro e Caldas e Paulo Cintra.

|

|

José Escada, S/ título, recorte branco, 1968. Papel recortado sobre papel, 31,5 x 48 cm. Col. Caixa Geral de Depósitos.

Laura Castro e Caldas e Paulo Cintra.

|

Shifting to a more descriptive panorama of the most important artistic production of this period, we should begin by referring and following a simple chronological order to a group of artists that we can gather within painting and figuration, although each with very differentiated courses and options. Joaquim Rodrigo, after beginning his career in the post-war years in an abstractionist vein, created in the 60s a systematic code of pictorial signs and rules of representation that he would maintain until the end of his life. António Dacosta, a historical surrealist, after abandoning painting in the 40s would come back to it in the 80s with a remarkable original trait. Júlio Pomar, who began in the 50s as a neorealist, would develop different painting modes through which he worked figuration, body and movement. Menez, who painted abstract landscapes in the 60s, would approach a more mythical and narrative figuration later on. Paula Rego, departing from the brutality figurations of the 50s, revolutionised methods and processes until she reached a painting with more classicizing resonances in which her great authoritive power is affirmed and reinforced, which brought about her full consecration.

|

|

|

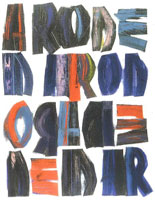

João Vieira, Uma Rosa É, 1968. Óleo sobre tela, 200 x 161 cm. Col. Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian / CAMJAP.

Mário de Oliveira.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Álvaro Lapa, Página, 1965. Flow-master, tinta de água e acrílico sobe papel, 61 x 43 cm. Col. particular.

Mário de Oliveira.

|

|

Another group of artists, whose public affirmation is set in the 60s, preferably insisted in an approach to painting through the analysis of its formal and structural constitutive elements. This group includes Ângelo de Sousa, António Sena, Jorge Martins, João Vieira and Manuel Baptista. The aspects that are at stake here are the place, the light, the colour, the sign, the trace. Jorge Martins researched on light and on painting itself, creating grids and small compartments in which he inserted stories, characters and objects, in which he interchanges with the representation of volumes and folds, referencing the cinematographic universe. Manuel Baptista, after abstract paintings of an informalist nature, employed diverse techniques from collage, relieves and object-paintings in the mid 60s to the use of the monochrome and cut-out canvases. It is also during this period that João Vieira would come across the theme that would be central to his entire oeuvre: the alphabet and the plasticity of the words, whether in his paintings or in his installations and performances. With his object-letters, Vieira introduces the "happening" for the first time in Portugal, as a result of his coming into contact with Vostell, in Malpartida de Cáceres.

These works would follow a more intellectualised and conceptualizing path, as for instances with Fernando Calhau, Pires Vieira and Michael Biberstein, at an early stage of his career. To mention a peculiar example of the convergence of writing and the references to literature, one should emphasize the name of Álvaro Lapa.

António Areal is another reference in the history of the Portuguese art of these times. Not only for his pictorial and sculptoric oeuvre, but also for his work of theoretical reflection, expressed in texts such as Textos de crítica e de combate na vanguarda das artes visuais (Critical and Combating Texts in the Avant-Gardes of the Visual Arts, 1970). After a first surrealist and gestualist stage of his career, he would approach the relationship between figurative and abstract art with paintings and objects clearly influenced by conceptual concerns.

Joaquim Bravo, with a literary education similar to Álvaro Lapa's and António Areal's, extended his artistic practices to painting, sculpture and drawing, producing a remarkable series of sculptures during the 60s.

A group that we can associate to a certain pop ambience in a very broad sense - which includes the "nouveau réalisme" and "narrative figuration" - allows us to gather the works produced in the late 60s and early 70s by authors such as Lourdes Castro, René Bertholo, Costa Pinheiro, António Palolo and Eduardo Batarda, which would follow very diverse courses. Lourdes Castro, René Bertholo, Costa Pinheiro, Escada and João Vieira along with Christo and Jan Voss, would form in Paris the group called KWY (Ka Vamos Yndo) and the magazine with the same name. The group's aesthetical solutions were presented in 1960 at the SNBA (National Society of Fine Arts).

|

|

Nadir Afonso, Espacilimitado, 1958. Óleo sobre tela, 80 x 147 cm. Col. Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian / CAMJAP.

Mário de Oliveira.

|

|

|

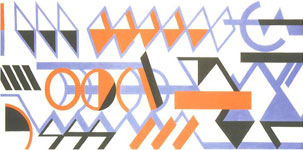

Artur Rosa, Entrada de Um Cubo Numa Malha Logarítmica (Explosão-Esfera), 1968/69. Técnica mista sobre alumínio, 350 x 1500 cm (ext. 600 cm). Col. Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian / CAMJAP.

Carlos Azevedo.

|

Still following this pop-related line, we can associate the works of Ruy Leitão, usually done on paper with very bright colours and recurring elements. His was a rich and personal pictorial universe that would be cut short by his death in 1976. António Charrua, after an Expressionistic phase would turn to the association of colours and abstract forms.

Rolando Sá Nogueira, a painter already active in the 50s, during which time he showed preference for a somewhat naïve figurativism, would then embrace in the 60s the aesthetics of pop art after his stay in London (1961-1964), expressed collages of great artistic freedom.

Nikias Skapinakis used a figurativism of very rich chromatics during the 50s, as a consistent alternative to the period's most common trends, namely neorealism, surrealism and abstractionism. In the 60s, he would create a series of landscapes and group portraits that can be read as a sociological portrait of the whole era.

|

|

|

|

|

|

António Areal, Mês de Marte, 1966. Óleo e esmalte sobre platex, 54 x 65 cm. Col. Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian / CAMJAP.

Mário de Oliveira.

|

|

Sá Nogueira, Highlife, 1964. Colagem e óleo sobre tela, 53,5 x 38 cm. Col. Centro de Arte / Col. Manuel de Brito.

DR/ Cortesia Galeria III.

|

|

Joaquim Bravo, The Hunting of the Snark, anos 60. Tinta industrial e colagem sobre papel colado em platex, 76,5 x 95 cm. Col. Maria de Lourdes Bravo.

José Manuel Costa Alves.

|

| |

|

| |

Eduardo Nery, Estructura Nº 10, 1968. Óleo sobre madeira com caixa em relevo, 125 x 100 cm. Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian / CAMJAP.

José Manuel Costa Alves.

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Ernesto de Sousa, Encontro no Guincho, 1969. Ernesto de Sousa e o actor João Luís Gomes.

Manuel Torres / Cortesia Espólio Ernesto de Sousa.

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Alberto Carneiro, O Canavial: Memória / Metamorfose de um corpo ausente (detalhe), 1968. Canas, fitas adesivas coloridas, ráfia, letras e algarismos, dim. variáveis. Col. Caixa Geral de Depósitos.

DR/ Cortesia Galeria Fernando Santos.

|

Noronha da Costa, one of the most important artists of the time, alongside being a painter, a sculptor, an architect and a cinema director, intensified his concerns through the sheer visibility and physicality of his objects. His works incorporate mirrors that allow for the objects to be representational of themselves but also to be used as the platform for playful forms and for appearing/disappearing spaces. By the end of the 60s the artist turned to a pictorial language, maintaining these visual explorations even if using "sfumato" or blurred ambiences through which one can picture fragments of people, places, landscapes, candles or other lightning elements.

This is the period when Costa Pinheiro creates his most known series - Reis (Kings) - and presents it for the first time in 1966 in Germany. In a certain manner, the author revisits in this series Portuguese history, using suggestive iconographical attributes for the several monarchs thus opening up the national collective memory theme, which, as it happened in the poetry of Fernando Pessoa, would characterise Costa Pinheiro's works in the next decades.

Employing a figurative vocabulary that is basically founded on naïve principles and skilled in many, variegated styles, references and ever renewed materials, José de Guimarães maintains a very personal artistic practice. Since then he has followed a consolidated and successful career both in Portugal and abroad.

Still another group of artists that one should mention is related to the specific formulations of op art. Their works are marked by mathematical rigour, the use of geometrical elements and by researches on the fields of perception and optical tension, Artur Rosa, also an architect multiplies and deconstructs forms in space with rhythms and movements that create perception and illusion games. Through a diverse work that comprised painting, drawing, photography and public interventions, Eduardo Nery's oeuvre was also constructed upon the repetition of elements and the examination of light and optical illusions. Eduardo Luiz, who lived in France for many years, created three-dimensional spaces in pictorial surfaces by using the "trompe l'oeil" effect in a particular manner, with Surrealist allusions to the suspension of time and space.

In Porto, the group Os Quatro Vintes (The Four Twenties) was formed, comprised of Ângelo de Sousa, Jorge Pinheiro, José Rodrigues and Armando Alves. They were associated to the Fine Arts School and lo the Árvore Cooperative - a space opened to experimentation and alternatives to the regime's culture. Between 1968 and 1972, combining their individual clout they attempted to reach substantial visibility, in order to call upon people's attention to the cultural weakness of the northern city and to reflect upon new visions of sculpture. Yet they were not looking for the assumption of a coherent, united visual program, as we would notice through the diversity of the individual courses of each one of the group's members.

Within the field of sculpture, João Cutileiro developed themes related to the human body and to sexuality and by introducing many innovative forms from which emerge warriors, trees and women. In 1966 the artist turns exclusively to working with marble. His education in London in the second half of the 50s was of paramount importance to his approach, and subsequently the whole country, creating new sculptoric languages and making Cutileiros a household name for the following generations of sculptors.

The 60s are referred to by some historians as being a period of ruptures. It was, undoubtedly, a moment of change but a change that went together with continuities. It was also the moment when Portuguese artists were able, simultaneously with the international languages of the time, to introduce aesthetic researches and formulations. This would result in very mature works and individual courses with substantial recognition. It is throughout these years that many artists' careers were drawn and made known, many of whom are active today and who would assume a preponderant role in the panorama of Portuguese contemporary art.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Eduardo Batarda, O Sr Professor C. J. P. Na Hora do Maior Movimento, 1965. Acrílico sobre madeira, 100 x 60 cm. Col. Mário Cesariny.

José Manuel Costa Alves.

|

|

Costa Pinheiro, D. Inês de Castro, 1966. Óleo sobre tela, 170 x 135 cm. Col. Centro de Arte / Col. Manuel de Brito.

Carlos Pombo da Cruz Monteiro - Arquivo Nacional de Fotografia.

|

|

João Cutileiro, Guerreiro com Caveira de Touro, 1963. Polyester, pó de bronze e fibra de vidro, 65 x 24 x 13 cm. Col. Dr. Mário Soares.

João Cutileiro Jr.

|

|

Armando Alves, Jorge Pinheiro, Ângelo de Sousa e José Rodrigues, Grupo Os Quatro Vintes em 1970. Col. Galeria Alvarez Arte Contemporânea.

Ursa Zangger.

|

|