|

The 80s

| |

|

| |

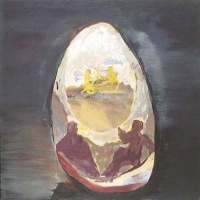

Pedro Casqueiro, S/título (detalhe), 1984. Acrílico sobre tela, 150x150 cm. Col. particular.

Abílio Leitão.

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

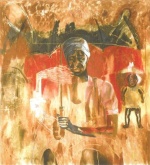

Pedro Proença, Prometeu, 1983. Acrílico sobre papel, 174 x 130 cm. Col. Fundação de Serralves.

DR/ Cortesia Fundação de Serralves.

|

The establishment of a democratic regime in Portugal made possible by the 25th of April 1974 brought about new cultural conditions, which on its turn allowed for the appearance and the swift recognition of a new wave of creators and cultural agents in the 80s. In the field of visual arts this decade was characterized by the emergence of a large and diversified group of artists with a strong, affirmative attitude in relation to their own works combined with a particularly dynamic cultural presence. At the same time a new wave of agents associated to the area from gallery owners to art critics (as Alexandre Melo and João Pinharanda, for instance) also emerged. These are people who have extraordinarily contributed towards the capacity of circulation and vitality of the scene, reflecting the international tendencies of the time where the growth of the popularity of visual arts was concerned.

As it should be evident the vitality of the artistic scene, which we have referred to and consider being quite characteristic of the period, was not exclusive to the emerging artists of the time. Quite the contrary, this was a state of affairs in which artists representative of very different generations and sensibilities were juxtaposed in the same setting and contributed to a body of work leading to a distinctively dynamic and diverse artistic scene. The 80s are a witness to the cross-pollination of some of the artistic practices inherited from the previous decade such as Post-Conceptualism with Helena Almeida, Alberto Carneiro and Fernando Calhau, for instances, or the new realities of the 80s, which showed a high plurality of people and resulted in a hybridization of aesthetic solutions.

However, a special place should be reserved to artists whose work and public recognition were already consolidated before the 80s but that would reach in this decade an outstanding notoriety and a renewed vigour. A few examples are António Palolo, António Dacosta (who resumed his pictorial activities), Paula Rego, Menez (who turns to a more figurative vein), Pomar (who evokes the great literary figures of the country), Eduardo Batarda and Álvaro Lapa. Nikias Skapinakis returns to landscape in this decade (Vale dos Reis - Valley of the Kings) and would continue that research until the next decade, abandoning the figurativism he pursued in the 60s and 70s under the strong influence of poster art.

Joaquim Bravo's work is recognized by this time: he developed a systematic research on formal inventiveness, which reached an extremely free, flexible and original non-geometrical abstraction. Also, due to his personal enthusiasm and pedagogical skills, from the late 70s onwards he constructed a circle of friends that included a number of younger artists such as Xana, José Miranda Justo, Pedro Cabrita Reis and João Paulo Feliciano.

The exhibition Depois do Modernismo (After Modernism, SNBA, 1983) organised by Luís Serpa brought to Portugal for the first time the issue of and the consequent debate on post-modernity, corresponding thus to the contemporary visual arts situation of a "return to painting", and the emergence of the transavantgardes, neo-expressionism, "bad painting" and new figurativisms. These movements were predominated by human figurativism and more often than not underlined by an impulse-driven spontaneity in its execution. This exhibition - most artists of which had been active in the previous decade, with the exception of Gaëtan and Pedro Calapez - was presented with parallel actions in the fields of contemporary dance, music, fashion and architecture. In the following year two other exhibitions would also contribute to the strengthening of such aesthetic diversity and the endorsement of theoretical debates: Os Novos Primitivos (The New Primitives) curated by Bernardo Pinto de Almeida in Porto and Atitutes Litorais (Coastal Attitudes) curated by José Miranda Justo in Lisbon.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Albuquerque Mendes, Nota de mil escudos, 1981/82. Óleo sobre papel colado em platex, 48 x 95 cm. Col. Banco Comercial Português.

DR/ Cortesia Galeria Graça Brandão.

|

|

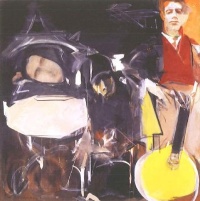

Julião Sarmento, Noites Brancas, 1982. Técnica mista sobre papel, 162 x 133 cm. Col. Isabel e Julião Sarmento.

José Manuel Costa Alves.

|

|

André Gomes, Cozinha dos Anjos, 1991. Polaroid / Fujichrome, 100 x 80 cm (cada) e 210 x 320 cm (dim. totais). Cortesia do Artista.

Cortesia do artista.

|

In this context, Julião Sarmento, who had made a name for himself as an author of post-conceptual practices, became the most internationally known name of Portuguese art due to his participation at the 1982 and the 1987 Kassel Documentas.

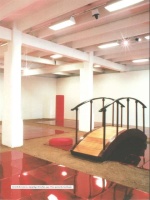

One may include in this dynamic period the works of very different types of artists. Gerardo Burmester unfolds his attitude and experience as an artist living with an unrelenting nostalgia for Romanticism's ideals of beauty and emotion. One must bear in mind his exuberant landscapes - the voluptuous usage of wood, leather and felt - in all the objects he produced by the late years of the decade. And in addition, the exquisite use of the varied colours and the overwhelming debauchery of reds and golds as well as the elegance of his drawing and the accuracy of the forms in his early 90s installations.

|

|

|

|

|

|

António Palolo, S/título, 1983. Acrílico sobre tela, 179 x 132 cm. Col. particular.

José Manuel Costa Alves.

|

|

Pedro Casqueiro, Sem Título, 1986. Acrílico sobre tela, 177 x 168 cm. Cortesia Galeria Filomena Soares.

DR/ Cortesia Galeria Filomena Soares.

|

|

Ilda David, S/título, 1989. Óleo sobre tela, 120 x 120 cm. Col. particular.

Laura Castro Caldas e Paulo Cintra.

|

Albuquerque Mendes finds in self-representation, mythical and religious figurations and evocations some of the strongest guiding principles of a work in which the practice of painting is combined with experiences in the areas of installation and performance.

|

|

|

António Dacosta, O Bailador, 1986. Acrílico sobre tela, 194,5 x 129,5 cm. Col. Fundação de Serralves.

DR/ Cortesia Fundação de Serralves.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Graça Pereira Coutinho, Letters to my mother, 1986. Técnica mista sobre tela, 210 x 166 cm. Col. Particular.

DR/ Cortesia Cristina Guerra Contemporary Art.

|

|

Graça Morais continues her successful career based on a figurativism with strong expressive intent, associating it to archetypes repossessed from a traditional rurality.

António Cerveira Pinto and Leonel Moura, who have always attempted to react through their careers and works to the successive turnabouts and changes of the aesthetic and ideological situations, were also important contributors for the debates on post-modernity and beyond. Moura's visual work was internationally recognised by the late 80s with the works in which he used photographic images of referential figures and icons from Portuguese, European and North-American cultural traditions.

In this decade, photography would increasingly become more integrated in the circle of the Fine Arts, particularly due to Jorge Molder's work. André Gomes is a peculiar case, in the sense that his different us ages of photography lead to a very personal albeit transdisciplinary universe. His work incorporated the technological, economical and media related determinations of the processes through which the imaginary is built through the use of instantaneous photography, polaroid, video, and the multiplicity of combinations of different types of photographs. Paulo Nozolino was also another name that reached a wide public recognition although his work is circumscribed to a more traditional and specific strand of photography, especially where its documental facet is concerned. Among many younger artists, photography was the privileged medium: such as Daniel Blaufuks who uses it in a more intimate perspective and Augusto Alves da Silva who employs it with a sociological mind.

The Encontros de Fotografia de Coimbra (Encounters of Photography in Coimbra), organized by Albano da Silva Pereira since 1980, which would lead to the present CAV (Centre for the Visual Arts), made a major contribution for the reinforcement of the national photography scene and at the same time it held many exhibitions of several international photographers.

One of the most outstanding characteristics of the art scene of the 80s was the vivid and media-savvy liveliness brought by the public presence of successive waves of new artists who made up several informal groups revealed in the decade through their exhibitions and through collective interviews. One must take in account however that what brought these artists together was more of a sharing common complicities and attitudes - for having studied together, for a desire to be promoted together - than for any aesthetic or programmatic affinities, as one would immediately realize as soon as each of these artists, individually, engaged in the pursuit of their own careers.

One of the groups that were active at the outset of the decade included, among many others, Pedro Calapez, José Pedro Croft, Pedro Cabrita Reis and Rui Sanches. They participated in many exhibitions but perhaps one of the most important ones was Arquipélago (Archipelago, SNBA, 1985) in which Ana León and Rosa Carvalho also participated. From this group, Pedro Cabrita Reis was an artist able to built one of the most consistent international careers of the country, making him one of the most known names of his generation.

Within the same chronological context, it is essential to refer to the work of other artists, such as Pedro Casqueiro, Ana Vidigal, Ilda David, Manuel Rosa and Pedro Tudela. Ana Vidigal brings painting and writing together, incorporating diverse materials in order to produce a universe of personal references filled with colour and rhythm. Ilda David's paintings have a strong lyrical vocation inspired chiefly by a literary imaginary.

|

|

|

|

|

|

José Pedro Croft, S/título, 1982. Escultura em mármore, 100 x 160 x 5 cm (base). Col. particular.

DR/ Cortesia do artista.

|

|

Graça Morais, Cabo Verde, 1988. Acrílico e pastel sobre lona, 200 x 185 cm. Col. Centro de Arte / Col. Manuel de Brito.

Carlos Pombo.

|

|

Álvaro Lapa, Os criminosos e as suas propriedades, 1974/75. Acrílico, tinta de escrever e cartolina platex, 63,5 x 121 cm. Col. Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian.

Mário de Oliveira.

|

The sculpture of Manuel Rosa is integrated in an area where memory, wandering, survival and premonition are present. Ever since his first individual exhibition in 1984 he has kept the exact same logic of processes of work, although coming closer and closer to a more abstract and reflective stance. His allusions to igloos, tunnels and houses are mainly evocative of symbolic places of imprisonment and escape, of formation and conservation. However, in his works of the 90s, the major themes were replaced by a more emotional, artisan-like approach, giving it an intimate, workshop-like dimension.

|

|

|

|

Júlio Pomar, Lusitânia no Bairro Latino - Retratos de Mário Sá Carneiro, Santa-Rita Pintor e Amadeo de Souza-Cardoso, 1985. Acrílico sobre tela, 158,5 x 154 cm. Col. Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian /CAMJAP.

Mário de Oliveira.

|

|

Leonel Moura, s/título (Portugal Dupla), 1987. Acrílico sobre fotografía e ferro, 110 x 155,5 cm. Col. Fundação de Serralves.

DR/ Cortesia Fundação de Serralves.

|

|

|

|

|

Fernando Calhau, s/título, 1988. Acrílico sobre tela e ferro, 86 x 169,5 x 11 cm. Col. Margarida Veiga.

José Manuel Costa Alves.

|

|

Eduardo Batarda, El Scotcho, 1987. Acrílico sobre tela, 150 x 200 cm. Col. Comendador Arlindo Costa Leite.

José Manuel Costa Alves.

|

As for Pedro Tudela, the very materiality of the body - with all its visceral and organic folds - was chosen as the polarizing axis of a work that brings together a material, sensual painting and a more sophisticated choice for multimedia installations.

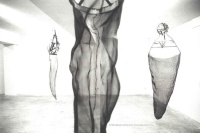

Making a name for himself in the same circle, a younger artist, Rui Chafes, became early on a main character of the field of sculpture, which still holds true today. Furthermore, we should emphasize his effective international recognition. Fernanda Fragateiro started with drawings but soon moved to the creation of installations with strong impact - works that assemble registers of intimacy and an intricate work of space articulation.

This very topic of space should also bring about the mention of Patrícia Garrido, who presents us with domestic spaces made significant through the body, and of Carlos Nogueira, who was driven by an aspiration to articulate the intimate space with both natural and man-constructed spaces.

|

|

|

|

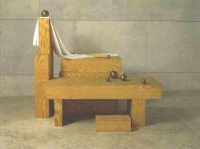

Rui Sanches, Mme. Récamier, segundo David, 1989. Madeira, pano e bronze, 164 x 180 x 167 cm. Col. Caixa Geral de Depósitos.

Laura Castro Caldas e Paulo Cintra.

|

|

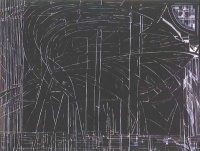

Pedro Cabrita Reis, s/título, 1987. Técnica mista sobre madeira, 240 x 240 cm. (4 elementos de 120 x 120 cm cada). Col. Fundação Luso-Americana para o Desenvolvimento.

Laura Castro Caldas e Paulo Cintra.

|

|

|

|

|

Joaquim Bravo, Arrepio ou a Escolha do Crítico, 1989. Acrílico sobre tela, 90 x 105 cm. Col. Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian / CAMJAP.

Mário de Oliveira.

|

|

Manuel Rosa, S/título, 1989. Calcário e anilina preta, 93 x 160 x 75 cm. Col. particular.

DR/ Cortesia Assírio & Alvim.

|

Still another wave of artists that needs mentioning appeared in the mid 80s made known through several collective exhibitions among which Continentes (Continents, SNBA, 1986), which brought together Pedro Portugal, Pedro Proença, Fernando Brito, lvo, Xana and Manuel João Vieira. This group's initial practice chose an immense visual exuberance, reflected in their stances through a somewhat blasé eclecticism where references were concerned, a strong, provocative and playful manner and a very evident intention to create ironic commentaries on the contemporary artistic scene. The work of Xana, a mixture of painting, object-making and installation, clearly revealed dexterity with colours and forms. Manuel João Vieira would become famous later on as a lead singer of several bands such as Ena Pá 2000 and a sort of cultural/political agitator branded by a personal touch of critical humour.

Where galleries and institutions are concerned, to put it briefly, we would like to highlight three traits of the Portuguese artistic scene of that time, which can be seen, perhaps among others, as causes of its structural debility. Firstly, we have the typical feebleness of the Portuguese cultural institutions, whether public or private. These are rarely able to survive the personal efforts, ideological enthusiasms, particular social dynamics or specific economical situations usually associated to the appearance of those very same institutions. After the customary vitality of their beginning they fail to secure an organized cultural base and a solid professional financial foundation. Therefore, some of them ended up disappearing or entering a phase of decline precisely in the moment when they should have entered a phase of maturity. The inconsistency of purposes by the State's and the public institutions' cultural initiatives and policies are also particularly evident and regrettable. Historically speaking these agents have been always characterized by the inability to draw goals and to adopt strategies and methods of organization and management that could promote a cohesive, consistent and effective cultural intervention of any kind, whether within the country or abroad.

| |

|

| |

Rui Chafes, Um sono profundo, 1988. 15 esculturas em ferro. Vista da exposição na Galeria LEO.

DR/ Cortesia do artista.

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Gerardo Burmester, Arquipélagos Vermelhos, 1992. Vista parcial da Instalação.

DR/ Cortesia Galeria Pedro Oliveira.

|

A second trait that is quite debilitating to the national artistic situation, and that stems from the obstructions, as it were, imposed by the State we just mentioned, is the historical inability of the Portuguese powers to assure the foundation of a public collection or a museum that could gather the most representative examples of Portuguese art of the 20th century. Simply put, the Portuguese State has no collection and no place to exhibit what is most significant in modern and contemporary Portuguese art. The crucial and elementary cultural function, a public function, of preserving history and didactically display a group of representative works of the contemporary artistic heritage has not yet been addressed. All the acquisitions of works, when actually done, were irregular, discontinuous and disarticulated. What the Portuguese State possesses and can exhibit publicly to the new generations as the examples of the 20th century Portuguese artistic creation is insufficient, and notoriously so. Nonetheless, as if replacing the State in this unaccomplished duty we should mention the existence of the collection of the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation and of a few other private collections.

These two traits trigger still yet another one, which is extremely serious and dangerous for the development of the dynamics of culture and the creative processes in Portugal: the sheer absence or extreme insufficiency of cultural transmission mechanisms through which the cultural practices and experiences that have been accumulated over time, and the very historical information and transmission, can be assured. Due to the absence or debility of these mechanisms - adequately revealed by the mentioned fact of the State's lack of response and responsibility and the persistent anachronism of the functioning models of the official artistic formation institutions -, the older generations of artists feel ignored, forgotten, abandoned and even despised, and the younger ones feel that they are building everything from scratch as if nothing ever existed before. The utter waste of knowledge, time and energy that this gap conveys is absolutely huge. Instead of a convergence of the generations, everyone spends precious time in repeating what was once said and done many times before, when they should be employing these ideas immediately for their development and unfolding them towards their ultimate consequences.

Before the 25th of April we had above all the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation and, on a smaller scale, the SNBA as the main centres of vitality in the Portuguese art scene. Later on the SNBA would lose this leading role and its contact with contemporaneity although it did present now and then important exhibitions. Gulbenkian, however, especially after the opening of its Modern Art Centre in 1983, but after a phase of a hesitant contact with the new situation of the 80s - of which we would like to mention the exhibitions Van Abbe and Diálogo (Dialog) as the exceptions - would become in the next decade informed by perspectives closer to the dynamics of its time-frame.

As for the art galleries, after all the cultural and artistic vivacity of the 60s and the brief period of euphoria in the art market in the early 70s, the sole surviving gallery opened throughout this time was III Gallery. The reason for this lies in the almost museum-like nature of the gallery's collection and the personal collection of Manuel de Brito. From the galleries that opened their activities in the 70s, and after a first phase branded by the social and political turmoil and by the absence of an art market, the continuity and the survival of the Módulo Gallery - and until very recently of the Quadrum Gallery - is but the proof of the too much weight that passionate and cultural aspects have taken in the motivations of their agents, as well as it makes up the logic foundation of their cultural prestige and their connotation as "avantgardes" that was recognised at the time.

By the mid 80s, we witnessed a moment of a higher dynamics due to the opening of several new galleries among which we will name two for very different reasons and that became the best image of the decade: the Cómicos Gallery in Lisbon, and the Nasoni Gallery in Porto. Other relevant examples are Valentim de Carvalho in Lisbon and the Roma e Pavia Gallery in Porto, renamed later on as Pedro Oliveira.

|

|

|

Rui Chafes, Ooglid, 1995. 6 esculturas em ferro. Vista da exposição na Galerie Declercq.

DR/ Cortesia do Artista.

|

|

Cómicos is a sort of cultural symbol of the decade. Its activity was intimately associated to a large number of names that comprised a group of artists with a stronger ability to consolidate their work in these last few years and to the aesthetic themes and debates that characterised those times, namely the issue of post-modernity. Nasoni is also a symbol but in a more economic point of view, given the fact it developed some of the most ambitious work ever made in the Portuguese art market. To be more precise Nasoni assumed and pushed forward that which we can call the Portuguese version, on a smaller scale, of the euphoria - notwithstanding its typical spiral of inflation and speculation - of the international contemporary art market of the time.

The concentration of the number of openings, growths, and "déménagement" of spaces in the second half of the 80s, added to the project of the National Modern Art Museum in 1989, founded within the Casa de Serralves, are very clear indicators of the growth of the national cultural and economic vitality where visual arts are concerned, and an obvious consequence of an undeniable, even if very modest life of the Portuguese art market.

As signs of a growing internationalization we should highlight the presence in Portugal of some solo exhibitions by foreigner key-figures of contemporary art and the regular presence of Portuguese galleries in international art fairs. A special mention should be given to the ARCO fair in Madrid: Portugal has participated in it since 1984 to our present times (and in 1998 Portugal was the guest country) which contrasts against the fact that between 1986 and 1994 Portugal did not participate in any way in the Venice Biennial.

|