|

The 90s

| |

|

| |

João Paulo Feliciano, The Big Red Puff Sound Site, 1994. Colchão em oleado vermelho, cheio com esferovite; 2 lâmpadas fluorescentes azuis; 6 auscultadores suspensos do tecto; leitor de cd. Banda Sonora: "Teenage Drool", Tina And The Top Ten. 5 x 5 m. (dim. da sala). Col. PCR

Pedro Falcão.

|

Within the international context the 90s would begin with a political turnabout expressed mainly in a critical attitude towards the neo-expressionist "back to painting" movement that essentially characterised the 80s. Although within the country there were some attempts to adhere to this change of discourse, even explicitly so by a few groups of artists, the truth is that the dissociation between what one is defending and postulating and the form through which one does it was quite evident. In other words, within the international scene the refusal to "objectify" the work of art was naturally expressed through a dematerialization, opening up thus a decade of a trend of non-objectual works of art whose forms of manifestation can be seen in a wider usage of video or video-installation and in new attitudes, namely a more stressed ethnographic stance with which the artists deal from now on with the production, the distribution and the consumption of the works of art.

Actually, the paradigm of the artist while an ethnographer was an attempt to rewrite the Benjaminian discourse of the "artist as a producer", replacing the Other by a cultural Other, whose alterity is defined not through socio-economical constraints but rather through identity terms. However, this Other understood as a cultural identity has never existed in Portugal, a country that became familiarized with the concept of "proletarian" solely in the 70s, exactly at the moment when Alvin Toffler's "third wave" made the very notion of work obsolete. This is also in a country in which, notwithstanding its colonial memory, there is, to this day, an absence of its discussion and in which history teaching follows strategies of mystification. Given the fact Portugal never had to deal with a really overpowering immigration wave or that it never had a really substantial feminist movement, Portugal remained in its isolation towards the outside, practically detached to the shock waves that rang out throughout the 20th century. Also due to the longevity of Salazar's regime, Portugal did not experience a period of its own modernity. Therefore, it will come as no surprise the fact that post-modernity entered its borders as an imported product.

|

|

|

|

José Loureiro, Minutos, 1996/97. Óleo sobre tela, 194 x 261 cm. Col. Banco Privado Português.

Vitor Branco.

|

|

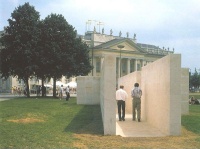

Pedro Cabrita Reis, Rio, 1992 (Documental). Mármore, 255 x 630 x 2530 cm. Col. do artista.

Dirk Pauwels.

|

At a national level, the decade was inaugurated with the 10 Contemporâneos exhibition (10 Contemporaries, Serralves, 1992) curated by Alexandre Melo which brought together 10 artists (Gerardo Burmester, Pedro Cabrita Reis, Pedro Calapez, Pedro Casqueiro, Rui Chafes, José Pedro Croft, Pedro Portugal. Pedro Proença, Rui Sanches and Julião Sarmento) presented as the main figures of the national artistic scene at the turn of the 90s. In the following year with the more specific goal of shaping an image that would brand the decade, the Imagens para os anos 90 (Images for the 90s, Serralves, 1993) was presented, curated by Fernando Pernes and Miguel von Hafe Pérez. For the first time a group of emerging artists was gathered, Miguel Palma, Paulo Mendes, João Paulo Feliciano, Fernando Brito, João Louro, António Olaio, João Tabarra, Carlos Vidal, Manuel Valente Alves, Daniel Blaufuks, Miguel Ângelo Rocha, Joana Rosa, Rui Serra and Sebastião Resende and others, amongst whom were some of the names that would shape the Portuguese art of the 90s.

|

|

|

|

Fernanda Fragateiro Instalação na Sala Sul, Museu de História Natural, Lisboa, 1990. Madeira, gesso, cimento, tijolo e alumínio, 25 x 10 x 5 m. Cortesia da artista.

Pedro Letria.

|

|

Ana Vidigal, s/título, 1991. Técnica mista sobre tela, 180 x 200 cm. Col. Centro de Arte / Col. Manuel de Brito.

Mário Soares.

|

|

|

|

Augusto Alves da Silva, Que bela família, 1992. Série de 6 fotografias, Fujicrome, 75 x 93 cm. (cada). Cortesia do artista.

Cortesia do artista.

|

|

This exhibition triggered a polemic that would cross the whole decade. To wit, two antagonistic forms to read the artistic practice: one associated to a more ahistorical, essentialist attitude and the other more alert towards the issues and the problems related to the social and cultural circumstances, that is to say, more engaged in an interventionist and compromised artistic practice.

The very fact that these points of view would become intensified are nothing but an example of the peripheral condition in which Portugal was and which it would be very difficult to relinquish. After all, it was (re)producing in Portugal a discussion that had occurred in Europe during the 30s. Meanwhile, in response to the mentioned dynamics brought by alterity, this decade would be defined by strategies of rupture, expressed in manifold ways: in the aesthetical, artistic context, in a stricter sense; in the generational context, with the generation of the 90s taking a stand against that of the 80s; and in the institutional context, with the students from Ar.Co (that would be rekindled by Manuel Castro Caldas as the new director) competing against the ones from FBAUL. Nonetheless, it is worth to mention that this dichotomist structure was only made possible due to the absence of a real alterity, a structure that ultimately disguises the absence of a real debate and of a real dialectics of production-reception.

On the other hand, and for reasons of pure sociological order, such as the shortening of career opportunities, the obstacles to become internationalized, and the market's debility, the 90s lived in the paradox of a noncorrespondence between intention and action. This is shown by the fact that the artists never really did abandon an objectual production. They even strengthened that practice through an institutional scale, i.e., the "museological scale", which reflects an attentive, accurate conscience on the existence and the drive towards articulating one's expression with specific "consumer audiences" and drawn by the new public institutions. This is a circumstance that is strengthened by a wider social phenomenon: in the wake of the 80s economic growth, Portugal witnessed the emergence of a new moneyed class, whose recent entry into a higher social status will be expressed through an extraordinary appetite for products that give prestige to the owners. If generally speaking this is a motivation for production the other side of the coin is that is also a conditioning factor, given the fact it acts out a demand for conventionality that is quite distant from experimentalist gratuitous actions, leaving no context whatsoever as to a legitimizing discourse.

|

|

|

|

Daniel Blaufuks, Auto-Retrato (Cérebro), da série O Livro do Desassossego, 1996. Duratrans e negatoscópio, 46 x 132 x 15 cm. (3 elementos). Cortesia do artista.

Cortesia do artista.

|

|

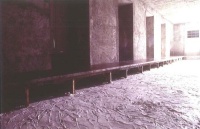

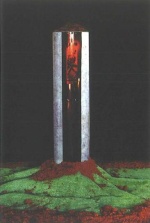

Carlos Nogueira, Chão de Cal, projecto 1992, realização 1994. Madeira, ferro, cimento, cal, luz e som dos passos, 24 m. x 9m x 4,20 m. Museu de História Natural / Sala do Veado. Col. do artista.

Carlos Nogueira.

|

Thus, and to a certain extent even against the most visible currents of the international scenes, the Portuguese artists that engaged their artistic practices in a more political positioning do so more in terms of the expressed content of their works. In this group, one may mention as examples the production of people such as Paulo Mendes, Pedro Cabral Santo or the duo Entertainment Co. (João Louro and João Tabarra). Most of these works are clearly objectual works where the plasticity is concerned; therefore, and ultimately, they reinstate the notion of art as a marketable product, notwithstanding its strong political stance and themes.

|

|

|

Rui Chafes, A Manhã IV, 1992/93. Ferro, 39 x 37 x 75 cm. Col. Fundação Luso-Americana para o Desenvolvimento.

Laura Castro Caldas e Paulo Cintra.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Ana Jotta, Roger, 1995. Toalheiro mecânico desactivado, toalha bordada, 78 x 37 x 21 cm. Col. Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian / CAMJAP

José Manuel Costa Alves.

|

|

In this sense, a large part of the Portuguese art produced in the first half of the 90s seems to be entangled in the paradox of a cynical, Warhol-like poise that nevertheless also avows a more critical, subversive, Brecht-like stance. However, it is at this conjecture that we must indicate two factors that should not go unnoticed. On the one hand the whole of the production of the 90s seems to be walking through the fine line between a clear critical stance and reiterative exploits. We may say that this hindrance, this appropriating of so-called imperialist signs but without transforming them into performative, useful tools, is something that we can see everywhere. Retrospectively, we come to understand that, the agents' conquests notwithstanding, such a broader social arrangement is quite conditioning to its reading. Appropriation does not mean the same thing in the 90s than it did in the 30s. On the other hand the decade's neo-conceptual wave generated a misunderstanding where the works' legibility was concerned. By postulating a certain hegemony of the subject, the perception of its other levels of meaning were some what obscured. This would be a problem far more felt in countries such as Portugal, whose peripheral role made it more vulnerable to information deficits or to a weak management of information, reproducing thus these hegemonic tendencies.

It is also worth noticing that the artists that have adopted an attitude which politicizes the artworks' form over its content, its technique over its subject, are the same ones whose personal and professional experiences are extended across the national borders, namely Júlia Ventura, João Penalva and Ângela Ferreira. It is through these artists that we see a certain continuity with the previous generation represented not only by themselves but by artists such as António Olaio, Ana Jotta or Helena Almeida, not to mention its rooting in the 70s via Ernesto de Sousa.

Returning to a chronological order, we must be mindful that Imagens para os Anos 90 was preceded by another exhibition that had been held at the Convento de São Francisco in Beja and in which the Portuguese artists João Paulo Feliciano and Carlos Vidal and the Spanish Pedro Romero and Siméon Sáiz presented their Manifesto, claiming for a politicised alternative to the Portuguese art of the early 90s. Also within the frame work of such a discourse, Jorge Castanho organised in the old Metalúrgica Alentejana, also in Beja, in 1995, the exhibition Espectáculo, Exílio, Deriva, Disseminação: um projecto em torno de Guy Debord (Spectacle, Exile, Dérive, Dissemination: a project on and about Guy Debord) with works by Fernando Brito, Carlos Vidal, João Felino, Paulo Mendes, João Tabarra, João Louro, Miguel Palma and Entertainment Co.

Although Portugal is still a peripheral country today, we cannot forget that it is also at this point that a series of new factors initiates a slow change of pace. As soon as 1993 an exhibition would introduce a whole new set of emergent artists to the Portuguese audiences, a set that would mark profoundly the international scene. We are referring to the exhibition titled Walter Benjamin's Briefcase, which was integrated in the 2nd Jornadas de Arte Contemporânea (in Porto) organised by João Fernandes. The exhibition was curated by Andrew Renton who presented some of the British artists that would become central and known as the world-famous Young British Artists (YBA): Douglas Gordon, Christine Borland, Graham Gussin and Jane & Louise Wilson, among many others.

A number of curators and institutions would keep up an effort through divulgation, partially bridging the gap between Portugal and the main European centres. We should also mention Miguel von Hafe Pérez, João Fernandes, Pedro Lapa, Delfim Sardo, Isabel Carlos and Jürgen Bock.

|

|

|

|

Ângela Ferreira, Portugal dos Pequenitos, 1995. 1 caixa de luz vertical (alumínio, plexiglass, vinil, lâmpadas; 20 x 42 x 180 cm), 1 escultura (madeira, PVC, mangueira; 850 x 120 x 80 cm), 1 plano do parque (papel, cor; 45 x 40 cm), 1 desenho (grafite sobre papel; 25 x 120 cm). Col. Banco Privado Português.

Ângela Ferreira.

|

|

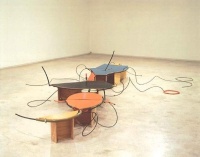

Miguel Palma, Ecossistema, 1995. Casulo em mica insuflada por ventilador, focos, ferro, alumínio, tubagens de ventilação, acrílico, temporizador, Kits de casas e fábricas à escala 1/100, 210 x 210 x 450 cm. Col. Institut d´Art Contemporain FRAC Rhôn.

DR/ Cortesia do Artista.

|

Isabel Carlos was the curator of the exhibition Depois de Amanhã (After Tomorrow) within the framework of the 1994 European Capital of Culture in Lisbon, which was held at the then, recently opened Centro Cultural de Belém. In the same venue, not longer after, an equally important event would be presented: Múltiplas Dimensões (Multiple Dimensions). Pedro Lapa begins at the Museu do Chiado a whole programme of exhibitions entitled Interferências (Interferences), which from 1996 onwards presented projects by artists such as Miguel Palma, Augusto Alves da Silva, Gillian Wearing, Jimmie Durham, Henrik Plenge Jakobsen and Stan Douglas. Deeply assimilated in the spirit of their times, these few iniciatives are islands of contemporaneity, as it were, in Portugal, by forwarding visions and tendencies that would shape the Portuguese scene to come.

|

|

|

|

Xana, Lar Doce Lar no Quarto 4, 1994. Pintura acrílica sobre MDF, 182 x 276 x 4 cm. Col. do artista.

DR/ Cortesia Culturgest.

|

|

Xana, Lar Doce Lar no Quarto 5, 1994. Pintura acrílica sobre MDF, 183 x 275 x 5 cm. Col. Mário Martins.

DR/ Cortesia Culturgest.

|

The outset of the 90s, with the first Gulf War, was one of generalised crises and economic recession. In this context, a new wave of galleries - Alda Cortez, Graça Fonseca and Palmira Suso - whose projects had begun slightly earlier, found themselves in a particularly difficult economic situation. Throughout the 90s, some of the most renowned galleries of the previous decade closed down, such as the Nasoni Gallery (a victim of a serious financial predicament), and the Valentim de Carvalho Gallery. The Hugo Lapa Gallery, which would substitute it, would also close down in 1997 alongside Alda Cortez and Graça Fonseca galleries. Meanwhile, another group of galleries, more prone to the actual market demands and with a more eclectic stance, stressing far more economic efficiency than cultural legitimation concerns, increasingly assume the leading roles of the scene. We should name two galleries in Porto, Fernando Santos and Quadrado Azul, along with a group of others that include André Viana (which would also eventually close), Canvas (replaced by the Graça Brandão Gallery) and Presença. However, there is a large contrast between the generalised closing down of galleries in Lisbon and what would occur in Porto, which becomes the main centre of galleries in the country during the late 90s. One finds in the northern city galleries such as Pedro Oliveira, a Módulo Gallery delegation and Zen Gallery, a sort of franchise of III Gallery. Suffice to say, in Portugal, these three galleries are the only ones that kept up their dynamic work they had shown in the previous decades.

|

|

|

|

Miguel Soares, Untitled (VR Trooper), 1996. Chapa zincada, acrílico, turfa irlandesa, relva artificial, VR Trooper, base rotativa, strobe-light, detector de movimento, 130 x 250 x 250 cm. Greenhouse Display, Estufa Fria, Lisboa. Col. Ivo Martins.

DR/ Cortesia do artista.

|

|

Pedro Tudela, S/título da série Rastos, 1997. Bobines de fita magnética e metais variados, dim. variáveis. Vista da instalação na Fundação Cupertino de Miranda, Vila Nova de Famalicão. Col. Fundação de Serralves.

ZM.

|

Beginning in 1992, Lisbon created an alternative map, due to the creation of the ZDB Gallery, whose role would be central for the consolidation of the paths of many of the artists that would appeal throughout the decade. In 1992, we witness also the emergence of an alternative to the artistic education offered by both FBAUL and Ar.Co, with the creation of the School for Visual Arts Maumaus. This school would later on be under the direction of Jürgen Bock and would become the sole responsible for the formation of a whole, new artistic trend, blatantly centre-European and well-versed in the concept of "Platform Art". That same year Pedro Cabrita Reis was invited by the Kassel Documenta and he opens an anthological exhibition of his work at Calouste Gulbenkian's Centre of Modern Art.

|

|

|

Miguel Soares, Untitled (VR Trooper) (pormenor)

DR/ Cortesia do artista.

|

|

In 1993, a self organised artists' group follows the footsteps of their British predecessors and takes on decisions relative to exhibition strategies. Among others, we have Paulo Carmona, Pedro Cabral Santo, Tiago Baptista and Paulo Mendes. After their first presentation with Set Up, held at the Faculdade de Letras de Lisboa, they would keep up a consequential programme of exhibitions that included, among many other collective shows, Greenhouse Display (Estufa Fria, 1996), Jetlag (at the rectory of the Universidade de Lisboa, 1996). Zapping Ecstasy (CAPC, 1996 ) , X-Rated (ZDB, 1997) , O Império Contra-Ataca (The Empire Strikes Back, ZDB, 1998) , (A)casos (&)materiais (CAPC, 1999 ) , PIano XXI (G-Mac, Glasgow, 2000 ) , Urban Lab - Bienal da Maia (2001), most o f them curated by Paulo Mendes or Pedro Cabral Santo. It would be through these exhibitions that a given number of artists would become known, bringing together new names such as Rui Toscano, Miguel Soares, Carlos Roque, Alexandre Estrela, and Rui Valério, to the already consolidated Ângela Ferreira, João Tabarra, Miguel Palma, João Louro, Entertainment Co., Paulo Mendes, João Paulo Feliciano, Fernando José Pereira, Pedro Cabral Santo, Augusto Alves da Silva, Rui Serra, Cristina Mateus and Miguel Leal.

|

|

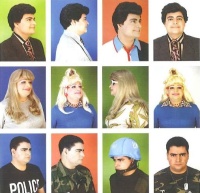

Paulo Mendes, L´Art de Vivre (Portrait) / Ken C´est Moi, Barbie C´est Moi, Action Man C´est Moi, 1997/98. Fotografia a cores, 12 partes, 39, 5 x 29, 5 cm. (cada), Ed. 6 exemplares. Col. Fundação Portugal Telecom; Col. Ivo Martins.

Arquivo Paulo Mendes.

|

|

|

|

|

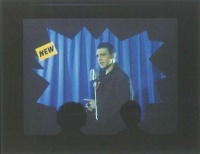

Pedro Cabral Santo, Exit (For You Guys), 1998-99. Vídeo, cor, som, 20´. Vista da projecção na Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisboa, 2002. Col. particular.

DMF.

|

|

João Tabarra, This is not a drill (no pain, no gain) (detalhe), 1999. Fotografia a cores, 180 x 275 cm. Col. Museu do Chiado - MNAC.

Cortesia do artista.

|

At the same time, yet another group of artists, mostly educated at Ar.Co, would become known such as Francisco Tropa, José Drummond, Edgar Massul, André Maranha, Rui Calçada Bastos and Noé Sendas, among others. In the beginning, we may say that there was a certain amount of rivalry between both groups, mainly due to each group's artistic schooling background. With the growing professionalization the competition would dissolve.

| |

|

| |

António Olaio, What happened to Henri Matisse, 1997. Óleo sobre tela, 90 x 250 cm. Col. Gerardo Burmester.

António Olaio.

|

Furthermore, the end result would be very different from the original grouping. One must bear in mind that the renewal of attitudes and processes are something done in tandem with the development of researches in the more classical, sounder disciplines. A special mention should be given to the deepening of the research on the contemporary possibilities of painting, in the diversity of its dimensions and its traditions, in many artists whose works had been developed with consistency. As examples, the unique tone evocative of the history of painting of Miguel Branco, the reinvention of landscape by João Queiroz, the exploring of abstract textures by João Jacinto, the surprising effect of Gil Heitor Cortesão's peculiar pictorial technique, the verve of the narrative pulsion-driven register of Fátima Mendonça, or the evolution of José Loureiro's work towards a systematic display through the practice of the never-ending potential of painting, beyond any formal codification.

Another major factor for the definition of the Portuguese art's panorama and its coefficient of professionalization was the creation of a Ministry of Culture in 1995 and its Institute for the Contemporary Art (lAC). Headed since its inception by Fernando Calhau, lAC would have a paramount central role in the growing verve of the production and divulgation circuits, which are nonexistent in the Portuguese arts, and in 1997 it would resume the national participation in the Venice Biennial (with Julião Sarmento curated by Alexandre Melo).

|

|

|

|

Alexandre Estrela, Biovoid, 1998. Fibra de vidro e holograma, 500 x 250 cm. Apresentado na Sala do Veado. Col. do artista.

Alexandre Estrela.

|

|

Rui Toscano, Infinity, 2001. Retroprojecção vídeo, DVD, 35´´, loop, 350 x 150 cm. Cortesia do artista / Cristina Guerra Contemporary Art.

Video Still - Cortesia do artista.

|

Other events are also developed in order to achieve the same result: from the creation of the Berardo Collection to the related opening of the Museum of Modern Art in Sintra, and the decisive opening of the Serralves Museum of Contemporary Art in Porto, with the international exhibition Circa 1968 curated by Vicente Todolí and João Fernandes.

Institutionally speaking, it is not an exaggeration to say that the second half of the 90s was definitely characterised by a huge progress. Besides the Serralves Foundation, we would witness the creation or the dynamizing of places such as Centro Cultural de Belém, Culturgest and Museu do Chiado without forgetting the role of the Luso-American Foundation.

A more conscious cultural policy of the cosmopolite contemporaneity allowed for the construction of a far sounder basis for circulation and curating (programming). In addition, and contrarily to popular belief, Portuguese artists were able to reach a reasonable institutional network of support, with a relative accessibility to scholarships, funding and subsidies. Conversely, the sheer lack of big collectors in the national territory was, and still is, a problem that cuts short the ambitions of the cultural agents, which are limited to a local horizon that, ultimately, is also a hindrance for the aspirations to become international of most Portuguese artists.

In this case, there is a severance between the State and civil society. Thus, Portugal still lacks the necessary means to affirm an image at an international level. Although it is true today those artists themselves are able to find their own accessibility channels and their own modes to become integrated in international circuits, it is also true that it is very difficult to keep up such a nature in the long run. Today, just as it happened before, contemporary art is an import product, and Portugal is not able to develop ambitious and consistent exportation strategies.

|